Initial Teacher Education – how can ITT providers ensure that belonging and decolonisation are included in their programmes?

By Catherine Bickersteth

Reflecting on my personal and professional experiences of the education sector, including my lived experiences as a pupil, a parent and a teacher, my thoughts have turned to how initial teacher education prepares future primary teachers in respect of the concept of ‘belonging’. When I use that term, I see it as encompassing equity and identity, which requires anti-racism and an understanding of what diversity in education looks like.

The face of ITT, like that of school leadership, is far from being representative of the diversity that exists in reality. A systematic look at whole school cultures and curricula needs to take place. This needs to be approached from the point of view of:

- the trainee teacher

- pupils

- understanding the impact of inclusive practice in creating a genuine culture of belonging

- professional development

Future teachers need to know that how they communicate with all the stakeholders in the school community needs to be inclusive and respectful. When behaviour is considered, it is vital that future teachers are aware of the negative impact of poor behaviour policies and attitudes – this must explicitly include looking at issues such as policies on hair styles.

In 2019 the Centre for Literature in Primary Education (CLPE) carried out its most recent research into representation of ethnicity in children’s literature. Their first report in 2018 provided evidence of the gap between reality and representation in books for children. The report (CLPE, 2019) reflects on changes made, and contains a thorough analysis of the questions that there are around the quality of representation in children’s literature, ranging from the quality of illustrations, characterisation, use of historical narrative, subject matter and genre.

The CLPE report is useful research to include in reading lists for teacher trainees, as it raises many thought-provoking questions and provides a source of examples of what children’s literature looks like when done well, to ‘reflect realities’. Without children – and staff – being able to use quality texts that include the diversity of ethnicity that we have, it is hard to grow a culture of belonging.

The subject specialist training and research that forms part of an ITE course needs to integrate questions about the curriculum. Teachers need to know where they can find resources to help them enrich subjects and to avoid the pitfalls of a narrow, Euro-centric, mono-cultural approach. Debates about decolonisation and the vocabulary within these debates need to be part of ITE courses.

Teacher trainees need to learn that there is an impact on the future outcomes for pupils if the curriculum is not sufficiently inclusive; teacher trainees need to know how to put into practice planning and teaching that avoids stereotyping or limits access on the basis of any protected characteristic; schools need to include the histories, contributions and voices of all, to equip pupils with an understanding of a complete British history. This decolonial lens needs to extend across the curriculum.

Thinking about these over-arching aims, I suggest here some ways that in-school and research-based teaching could be devised to address these areas.

Behaviour Policies

How far are the school’s policies anti-racist? For example, what are the school uniform policies? Does the school ensure that no one will be at risk of sanctions based upon their protected characteristics?

Do trainees understand the micro-aggressions based on ethnicity that adversely affect people?

Research uniform policies and how they impact on pupils with particular protected characteristics. An example of this is that for some trainees, their own lived experience will mean that they are unaware of how far people of Afro-Caribbean descent suffer due to some preconceptions based upon natural hair care. There are still cases of children facing sanctions which are based upon ill-conceived uniform policies. (Maxwell,2020) How many trainee teachers are also being negatively impacted by a dress code for staff which may be making them feel that they have to confirm to expectations which are go against their protected characteristics? The Halo code is aimed at avoiding discrimination based upon hair type and can be researched here https://gal-dem.com/the-halo-code-hair-discrimination/. A report into tackling Islamophobia in schools considers ways in which inclusive practices can be used. (NASUWT,2018)

An anti-racist educator will learn how their own behaviour can influence the children they teach and it is vital that teachers are provided with the tools to avoid making any child feel that they do not belong, and that teachers recognise how to educate children to respect others.

Are trainees aware of how adultification of black children can happen in educational settings, and the risk this poses for black and mixed-ethnicity children?

School and classroom environments

Are school positions of responsibility and representation for pupils accessible for all – for example, School Council representatives, representing the school in wider extra-curricular activities?

Who is represented in images in school displays and resources?

What evidence is there of a range of diversity in the authors of the reading material made available in school?

How do pupils learn about the concept of Empire, colonisation and migration in the school curriculum?

How do extra- curricular and enrichment opportunities actively represent role models from the global majority ?

How does each subject area embed diversity throughout the curriculum, not just as an add-on, or a themed day?

Curriculum

Each school will be giving a different experience for the trainee and practices in schools will be at vastly differing levels of curriculum development. For primary school trainees, the ITT provider must provide a consistent approach across the whole cohort. Primary school teachers need to develop subject knowledge in such a range of subjects that their subject knowledge is not necessarily developed to the extent that a secondary trainee teacher will have in their subject area. Nevertheless, it is important that primary school teachers understand how to teach in ways which actively provide rich and relevant subject knowledge, including all voices.

Furthermore, there needs to be a clear research-based curriculum which educates trainees on decolonisation. With this sound basis, trainees will be equipped to use this knowledge in school and can reflect upon the practice that they experience in school.

How can the curriculum content include untold stories, avoid being Eurocentric and teach pupils about the history of empire and colonisation?

What is included in the subject specialist teaching that primary trainees have, which explicitly consider decolonisation as applicable in that subject?

When are trainees given time to research the issues in education that relate to decolonisation?

Are teacher trainees aware of how to source a diverse range of texts, in terms of the authors and not only the content?

Religion

Does the school have an inclusive prayer area?

How does the school accommodate and support pupils who observe fasting for religious reasons?

How do school schools ensure that FSM provision is made available for children who are fasting?

How do pupils learn about world religions?

References

CLPE ‘Reflecting Realities report 2019

Maxwell, E What next for schools after hair discrimination case February 2020

Preventing and Tackling Islamophobia NASUWT 2018

Further reading and videos

Arshad, R Decolonising and initial teacher education Race.Ed Sep 2020

Chamberlain, N Diary of a Black Mathematical Modeller: My Black Lives Matter’. October 2020

Keval, H ‘Navigating the ‘decolonising’ process: avoiding pitfalls and some do’s and don’t’s’.

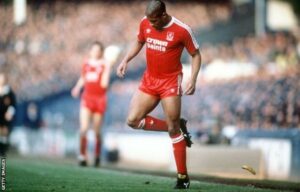

It's Coming Home...

By Adam Vasco

Adam is a Lecturer in ITE (Primary/Early Years) at Liverpool John Moores University

It's Coming Home... Unfortunately, when I say ‘it’ I am referring to racism and when I say, ‘coming home’, it never really went away.

It is Monday 12th July 2021. The dust is just settling on the first major final for the men’s English football team in 55 years which sadly ended in tears. Let me say this right from the outset, as is typical with many people in our city of Liverpool, I identify as “scouse” and not English. The scenes from last night’s game only further compound this. However, this rainbow-armband-wearing, free- school-meal fighting, knee-taking team had me interested. In their manager, Gareth Southgate, I had been won round by his leadership qualities, his humility, and values. It comes to something when the manager of the men’s England football team shows more leadership than the Prime Minister, but this is where we are.

As Bukaya Saka stepped up to take what would become England’s final penalty I had a sinking feeling. Not because I thought he would miss, but I knew that if he did, three black players would be held responsible. It was the first thing I said to a room full of white friends. They’re good people, that fact had not crossed their minds. This is privilege. The same privilege that was afforded to Stuart Pearce and now manager, then player, Gareth Southgate when they missed penalties in previous tournaments. Yes, they received criticism, but none of that was as a result of the colour of their skin.

The response was inevitable. In a country where our leaders criticise taking the knee, describe Burkha-wearing women as ‘letterboxes’ and use language such as ‘picannies with watermelon smiles’, racism has once again been legitimised. For today at least, most people will share some sort of outrage or denouncing of racism. However, this is not enough and clearly, this will do little to address or change the racial inequalities that exist. One of my childhood heroes John Barnes commented;

Football can do nothing to solve the ills of the world. What we’re saying is they score, we’ll support them, and if they don’t they’ll get racist abuse. We have to stop feeling football can solves this problem. Society has to stop it.

The history books tell us we have been here before:

- In the UK alone, we can go back to the post WW1 race riots, a shortage in jobs meant Jamaican soldiers were blamed for taking ‘their’ jobs.

- Post WW2, the Bristol Bus Boycott. Black people from Africa, the Caribbean and India were asked to rebuild the country (just like my Grandfather Abe who arrived from Lagos) but were not permitted to drive council owned buses.

- The Immigration Act of 1971 stripped Commonwealth citizens of their right to remain in the UK and restricted rights, something Priti Patel is seemingly trying to do again now, and let’s not mention the Windrush generation….

- Stephen Lawrence was murdered in 1993 but the perpetrators only convicted in 2012 with the Macpherson Report describing ‘institutional racism’.

- Here, only a matter of miles from the house in which I sit there were the 1918 race riots long before the Toxteth riots of the 1980’s.

- In 2005, shortly after the birth of my son and in the Huyton community in which we lived at the time, Anthony Walker was brutally murdered in a racially motivated assault. Sadly, I could go on.

Racial inequality is not a new topic, far from it. There is some debate to exactly when the term ‘white’ was invented as part of a ruling class, but in both David Olusoga’s and Theodore W Allen’s works, it would appear that it was around the early 1600’s. The rest is quite literally history.

We need not look back any further than the start of Euro 2020 and the response to players taking the knee to see this issue is as prevalent as ever. The irony of Home Secretary Priti Patel labelling this as ‘gesture politics’ and then a matter of days later donning an England shirt for a photo op is not lost on many of us. However, as shocking as this sounds, I find myself agreeing with Priti Patel, after all, even a broken clock is right twice a day. As the England team proudly took the knee, the question I have is this. Does sport care about equality? Do these gestures have any impact and what can we learn from this in the context of education?

Nesrine Malik wrote in The Guardian

‘But still we argue over the most basic ways of showing support for these causes, such as taking the knee.... What is becoming clear is that there is broad consensus that racism is bad… but very little appetite for actually doing anything to make the world fairer or more accommodating.’

Why is that? I would suggest that this is because to do something that tackles the actual issue it would impact on the bottom line. It would dent profits and that cannot be allowed to happen. What is the bottom line in terms of education? Knowledge!

I am fortunate enough to be part of an institution which is committed to challenging racial inequality. One way in which this is happening is through an institution wide decolonisation of the curriculum (DTC). However, my fear is that without the right guidance, self-reflection, education, understanding and knowledge, this work will become an empty gesture. Now, let me be clear. I am not saying I do not believe in the decolonisation and development of anti-racist curricula, that would be insane. I am a huge fan of this work; the recent research from the Runnymede Trust highlighted that less than one percent of authors studied at GCSE English Literature area from an ethnic minority background. However, I do question whether decolonisation goes far enough. Whether that in education it has become the taking of the knee.

Educational establishments are often a direct result of colonisation. That is okay. We must not rewrite history but learn from it. However, as School’s rush to decolonise their curricular should we ask the questions who is doing that and for whom? My experiences are this is a predominantly white staff, teaching a predominantly white cohort of students so surely something is afoot somewhere?

Our own website gives some history to LJMU:

‘We can trace our roots back to the Industrial Revolution. In 1992, we became one of the UK’s new universities, taking our name from one of Liverpool’s great entrepreneurs and philanthropists, Sir John Moores. Our current incarnation as a modern civic university demonstrates that we haven’t lost the pioneering zeal of our founding fathers and like them, we still believe that ‘knowledge is power’.

‘Knowledge is power’. One could argue that the system is designed to keep that power at the hands of the powerful. The uncomfortable truth for the predominately white workforce is that education is white. It has been racialised as white. It is structurally and inherently advantaged to those who are white. That is not exclusive to education, as Reni Eddo-Lodge says in her book ‘Why I am no longer talking to white people about race’,

'Whiteness positions itself as the norm, it refuses to recognise itself for what it is, it's so called objectivity and reason is it's most potent and insidious tool for maintaining power... it is a problem as we consider humanity through the prism of whiteness'.

Of course, in last couple of weeks we have seen the culture war rage on as the detriment of the white working classes was highlighted. I know, or certainly hope I am preaching to the converted here when I state the obvious fact class and race are inextricably intertwined. The racialisation of class is nothing but a culture war designed to stoke the flames of division. Or as Reni-Eddo-Lodge puts it,

‘sticking white in front of the phrase ‘working class’ is to make assumptions about race, work and poverty that compounds the currency like power of whiteness’.

Why in Liverpool are there so few teachers from diverse, not racialised as white backgrounds? Why in the institution I work in are there so few students from diverse backgrounds? Why do people from ethnically diverse backgrounds choose not to become teachers? Why is our own staff white? Why when I am writing sessions and am desperate to ensure that the materials and sources, I use are representative do I struggle to find black and brown academics writing about anything other than race? Is it some sort of invisible barrier? Or is it a system designed that way? We must acknowledge the systemic problems that are entrenched in education. Far from the being the solution, I would argue we are right at the epicentre of the problem. I am part of that problem and it hurts me to say that, after all I am of mixed-heritage. With my Nigerian grandfather, should I have been good enough to represent a country at any sport, I would’ve been a Super Eagle, no doubt about that. Although nothing on the scale of the abuse Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukaya Saka are currently facing, there have been enough events in my life which have told me that I don’t quite belong. I say this, as despite this, I acknowledge I am part of the problem, we are all part of the problem.

There is no doubt that decolonisation of curricular can be a crucial step in making meaningful change. I would urge all schools and educators to engage in this work. ‘Diversity in Schools: A Little Guide for Teachers’ by Bennie Kara is a great starting point, giving practical suggestions we can all put into our teaching. ‘Equitable Education’ by Sameena Choudry is also an essential text. As it says on the front cover, ‘What everyone working in education should know about closing the attainment gap for all pupils’. All schools and educators should buy, read, implement and integrate David Olusoga’s ‘Black and British: A Short Essential History’ into their curriculum. Colleagues should watch Pran Patel’s Ted Talk on Decolonisation of the Curriculum and all schools should challenge themselves to make sure their books are representative. The ‘I See Me’ blog by Twitter’s Mister Bodd is a great starting point for this. A colleague recently said, ‘in a sentence I want all our staff and students to make sure that representation is in all we do.’ I cannot find fault in that sentiment at all, in fact it is imperative that we must do this. It is our job!

However, DTC will not address the inequality that exists in education. It will not get more people into teaching. It will not increase the numbers of black and brown academics interested in the field of education. Therefore, the danger is that just like footballers taking of the knee that our good intentions end up as gestures or tokenistic performance politics that do not address the actual issues.

I return to the words of Nesrine Malik;

‘Liberal goodwill towards causes and general cluelessness about structural remedies mean we live in a climate where we seem to be talking about these issues all the time, creating the impression of a society saturated with sympathy and solidarity, but really quite hostile to change.’

We seem to be standing at yet another crossroads. This time it must be different, after all, how many more ‘years of hurt’ can we suffer?

References

Barnes, J. (2021) [Twitter] Monday 12th July. Available at: https://twitter.com/capitallivnews/status/1414488098243809281?lang=en (Accessed 12/7/21)

Choudry, S. (2021). Equitable Education: what everyone working in education should know about closing the... attainment gap for all pupils. S.L.: Critical Publishing Ltd.

Eddo-Lodge, R (2019). Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Kara, B. (2021). Diversity in schools. Los Angeles ; London: Corwin, A Sage Company.

Malik, N. (2021) ‘Are there limits to using celebrities to discuss race and mental health?’ The Guardian. 7th June 2021

Olusoga, D. (2020). Black and British: a short, essential history. London: Macmillan Children’s Books.

Anti-racism in a predominantly White-British School

By Louise Jaunbocus-Cooper

Louise Cooper is a Deputy Headteacher in a school where 84% of their pupils are White-British. Many have argued why is she addressing anti-racism, but Louise argues this is where it needs to be done. Here she shares what she’s learned and how proud she is of her pupils.

View the blog on Nexus Education.

Reflections on the 1%

By Louise Jaunbocus-Cooper

A fantastic session for our first in conversation with the 1%- we had 18 mixed race educators/allies on the meeting. My initial thoughts were- “phew/yay people logged on” …closely followed by… “Have I ever been around so many mixed-race people in my entire life? No!!!”. It was so nice to see people that were “like me”. Some looked a bit like me, most of course didn’t, but it was hugely comforting and immediately felt like a safe space.

So, what did we talk about and what did we learn? Here is a summary of the discussion and the contributions made by all.

- That 1hour 30minutes is not enough

- That we all have such different stories to tell on our journey to leadership.

- The one that was an imposter- using her “white-passing privilege” to stay under the radar, the guilt she feels, that only when she “made it” to the top, she started to bang the drum of anti-racism. How can we make sure people feel able to speak up early on in their careers?

- The one that never gave up- always working harder and often better (in terms of proven impact) but often overlooked for promotions that went to white, male colleagues. The intersectionality of gender and race.

- The one who felt the burden- that once you are at the table, it feels great, but you feel like you still have to conform, to sound like everyone else. When you make suggestions, you look like a troublemaker. The realisation that the institution is not willing to change, just appear more diverse. Those who look to you for leadership, see a “sell out” and so resentment burns. Leaving you isolated.

- The one who feels pride- that she is the one that will arrive at your school and be the face of her Trust. The first person to fill her role, never mind being female and mixed-race.

- How we can help to develop a better understanding of being mixed heritage and that it doesn’t look like one thing, sometimes it’s “unseen.”

- We agreed that Governance is key- to ensure diversity at the top is not just about senior leadership but governance too. Can anything really change until we change the racial makeup of those who appoint leaders?

Points that were submitted and we barely got time to discuss:

- Should we have to define ourselves? What do we call ourselves... should we have to explain why we define ourselves in the way we do? How do we respond to micro-aggressions- Where are you originally from? Your name is hard to pronounce. Great someone like you is in leadership…and so on.

- What about where other factors intersect - increasing age, disability, gender etc.?

- White people trying to work out how ‘black’ you are ... are you loud (aggressive) strong, quiet, reserved, what are your “black characteristics” and how black are they? Who you chose as a partner often being a measure of your ‘blackness’.

- The same above but from black/brown people ... almost like a constant ‘test’.

- Does all the above actually impede progression? Do we spend so much time navigating the above, that sheer fatigue and exhaustion leaves little room for ambition?

- Could there also be a degree of envy in some ways from both sides? We could be said to have more privilege than our black and brown peers are potentially able to occupy white spaces with less discomfort. White people perhaps envy the duality (or more) we have... ‘between camps’ as Paul Gilroy put it.

- Of the 1%, what are the retention rates? Are BAME staff that are mentored by BAME staff more likely to achieve success?

- What are the reasons BAME and Mixed Heritage people give for leaving an organisation? Those that cite discrimination - who follows up, if at all?

- Would mentorship of BAME and Mixed Heritage people by other BAME people in role. Will this help make the 1% bigger?

- How far does psychometric testing/traditional questions discriminate against those from other cultural backgrounds?

- How far does having an accent encourage prejudice despite that person often being probably able to read, write and speak multiple languages?

The discussion was so insightful and we now pose more questions than we have answer to…so the real work begins…

Thank you for co-hosting:

Shonagh Reid, Cassie de Gilbert, Sumeya Bhikhu, Marcus Shepherd

And thank you to the first founder-members of “The 1%”:

Ramon Mohamed, Claire Lotriet, Sharifah Lee, Julie Nisbett, Ki Dara, Azuraye Willaims, Claire Bale, Kat Rodrigues, Saira Ibrahim, Aimee Perkinson, Mumin Humayun, Camilla Small, Nazma Meah, Raj Unsworth, Edyta Ballantyne, Homaira Ibrahim, Esther Mustamu-Daniels.

Want to be a member of “The 1%”, get in touch.

The Sewell Report

By Claire Bale (@bale_claire)

The hot topic that brought the MixEd community together for our first event.

April 2021

Many of us have been deeply affected by the Racial Disparities Report by Dr Sewell. For many, including myself, it evoked an emotional response. As a person of colour, working in diversity and inclusion, the MixEd webinar to discuss the report was the safe space I needed. It provided a place to learn more, to ask questions, support others and to hear from the experts.

Co-founder, Marcus Shepherd, chaired a fascinating panel of diverse voices sharing their views on the report. This included MixEd co-founder Louise Cooper, Raj Unsworth, Pauline Anderson OBE, Christie Spurling MBE, Alison Kriel and Shonagh Reid.

We covered a lot, because the Sewell Report is BIG news. Both the panel discussion and the accompanying chat were full of vibrancy and energy. I won’t be able to cover everything here, but I’d like to share the key elements I took away from the evening in this short blog post.

I hope it will help to summarise an information rich evening and inform people who weren’t able to attend.

I also hope that it helps those who are feeling frightened by the implications of the report, who feel their lived experience has been dismissed, who feel they are not listened to, and are scared by the green light that seems to have been given to racists here in Britain, to know that we are here. All of us who are dedicated to antiracism, including the MixEd community, are more committed than ever to support each other and to drive change.

A “lazy report” designed to re-direct the narrative

Most of the webinar’s attendees are teachers. They know what a poor piece of work looks like. They can spot contradictions, lack of evidence and omissions a mile off. As Louise Cooper explained, to her, this report is “lazy”.

Selective subjects – there are many important subjects being discussed in the public domain. Islamophobia, intersectionality, Grenfell, Stephen Lawrence, Covid deaths, death in childbirth. It feels obscene to list all of these huge, tragic and important topics in one sentence. These are just some of the topics that are not addressed/or glossed over in the report.

Lack of evidence - the report is full of stats, but with no analysis of the cause. It consists of sweeping statements, stereotypes and the ideological views of the writer, with no back up from individuals’ experiences- as these are dismissed.

No root-cause analysis – as the panellists explained so well, data only presents the facts. To understand a situation, a report needs to ask the questions why, and then ask why again. It also needs to explain accountability. Dr Sewell’s report does not do this. It states that Black Caribbean families are often “broken”, for example. It doesn’t interrogate the reasons why. It mentions the distrust that people from ethnic minority communities feel towards British police and government. It doesn’t explain why this is the case. This limits the usefulness of the findings and provides no insight into how society can progress.

Yes – we are allowed to feel emotions

Panellists and attendees felt safe in the MixEd community. Away from the fear of judgemental tropes, we felt able to share our emotions. Individuals used words such as “gutted”, “gas lit”, “deeply disappointed”, “insulted” and “hurt”.

A concern shared by the MixEd panellists was around the permission the report will give to racists. At best, it gives people the excuse not to do anything about racism, because it conveniently says that there is no need. At worst, it adds fuel to the fire of racist hatred by furthering stereotypes, pitting ethnic communities against each other, and giving rise to the harmful and dismissive description of “angry Black people”.

We spoke at length about the disappointment of the missed opportunity of the report. As Christie Spurling MBE explained, this was a chance to say “this is what’s happened in the past, this is what will happen in the future.” And how powerful would that have been? To ensure that people who have struggled feel heard, and to inspire all of us, and especially young people, that their country is determined to do better.

What next?

A question that ran through the evening, right from the beginning, was “are there any positives in this report?” It was a tough question, but we all agreed that it brought us closer together. Everyone involved in last week’s webinar is committed to antiracism. By bringing us together, the MixEd team have helped us to find support from each other. Our resolve is strengthened. We know that there is work to do, maybe more than we thought, but we’re up for the challenge.

"Sinking into the Stereotype"

By Louise Jaunbocus-Cooper

Names have been changed to protect identity.

About Jordan

Jordan is in Year 10 and attends an oversubscribed, non-selective school in an affluent area on the outskirts of Manchester. The school profile is predominantly White-British.

Jordan came to this area when he was in Year 3 from Stretford, an inner-city and ethnically diverse area of Manchester.

Jordan has a White-British mother and a mixed-race father (White- British-Jamaican). He has a younger brother who has a different father (of Ghanaian heritage).

His stepfather is currently in prison for a serious crime. Jordan’s biological father has also served time in prison and separated from Jordan’s mother before Jordan was born.

One-to-one Jordan is a charming young man, with a very good sense of humour, a cheeky persona and a disarming smile.

He is however on his final warning before a permanent exclusion, due to persistent defiance and use of violence.

Out of school, Jordan has recently been caught by the police with cannabis.

Due to social services involvement, Jordan attended school during all periods of school closure and behaved immaculately.

Jordan and I met to talk about being mixed-race, what followed was an hour-long conversation with me frantically scribbling notes. I was unsure how to present our interview, but as I looked over my notes, I could see I’d used speech marks for certain things Jordan had said. I had written them verbatim, as they captured everything Jordan was trying to say in that moment.

These now form the headings of his account.

“I felt like I belonged, as people looked like me.”

We kicked off by exploring Jordan’s heritage. I asked if he felt a connection to Jamaica. The answer was an emphatic yes, ever since he visited a few years ago on holiday. Jamaica is a “sick place” (the jury is still out as to whether the Jamaican tourist board will adopt this slogan). His mother and stepfather had taken him to Dunn’s River Falls, which is the area his paternal family originate from. Jordan loved Dunn’s River Falls and climbing the waterfall. Steel drums made him feel happy and he could see more people “like him”. I asked him what he meant by that and he clarified many of the workers in the hotel were black but paler “like him”.

“I didn’t understand, why wouldn’t they pass me the ball?”

We began to talk about Jordan’s early life and his earliest memories of being aware he was mixed-race. This was in Year 3. Jordan loves football but noticed other children would not pass him the ball. He remembers trying to compensate by being overly generous with his own passing, but to no avail. This made Jordan feel angry and frustrated but also really confused. He just did not understand why they would not pass him the ball.

“What country was I supposed to go 'back to'?”

Things came to a head, when the popular boy told Jordan to go back to his “own country”. Jordan recalls not knowing how to react, as he wasn’t sure what country they meant. Eventually this led to feelings of anger. He had not faced this issue at his previous primary school where there were lots of black and mixed-race boys. I asked if there any other mixed-race boys at his primary. “No, just an Asian kid, but he liked being on his own and why would we be mates just ‘cos we were both not white?”. I asked Jordan if he had told his teachers about this incident. “Nah, it would have made it worse, there was no point”.

“How can you get us mixed up? We look totally different…”

We took the conversation to secondary school. What has his experience been? Immediately Jordan says he gets sick of teachers getting him and his best friend (also mixed-race) confused. Jordan cannot understand this, as he is tall with short hair, and his friend is shorter with curly hair. Jordan has concluded it is because they have similar skin colour. This makes him angry.

Jordan stated he has served time in the school’s Inclusion unit for something his friend had done. Why? I asked in astonishment. “’Cos he is my mate… I'm not snitching”. He tried to jog my memory of the incident, where a boy had been punched and hurt as part of a fight. Jordan stated it was his friend that caused the injury, but he was blamed, “they got us mixed up again”. Jordan took the punishment. Noting my shocked expression, “Miss it is fine, I was there, and I was fighting too, I just didn’t throw that punch” I asked why he didn’t speak up. “What's the point in telling a teacher?”.

“I’m sick of last chances; I’m not letting it happen.”

We talked about Jordan’s final warning. He knows he really is close to being permanently excluded and he understands why the school will have little choice if he carries on. He does not want this to happen. “When I was in Year 6, I wanted to go to a school in Stretford, but I know this school is better.” Why? “The teachers are good, and the school is strict, I need that”. Jordan is adamant he won't let a permanent exclusion happen. I remind him statistically he fits the profile of someone who might be permanently excluded. He knows because the Headteacher told him this (in the context of not wanting Jordan to be part of those figures) and it has “stuck in my head”. Jordan knows the Headteacher and the staff who work closely with him do not want him to go. However, a look at Jordan’s behaviour log makes for worrying reading. There is a litany of defiant and aggressive (verbal and physical) behaviour towards staff and students. His last 5-day fixed-term exclusion was for a nasty (and unprovoked) assault on a fellow student after school in a local shop.

“I’ve sunk into the stereotypes.”

We talk about this “profile” he might fit. I tell him I don’t want him to go, but I fear he will do something stupid, like bring cannabis into school. He’d never do that. What if it's still in your coat from the weekend? It could happen, a stupid mistake and you know we will have no choice. Some things are black and white (we both laugh at the accidental “pun”). Jordan is so honest, “I’ve sunk into the stereotype”. He has already been picked up by the police with cannabis on him. Why? “It’s what people expect of me. It's hard not to just go along with it”. Jordan says he gets stick for “acting white” because he doesn’t “rob”. Sometimes he thinks it would be easier to go along with it. He feels angry and can't control his temper. The “slightest thing gets me angry- I can't control it” Are you angry about racism? Yes, but other stuff too.... like my Dad.

“My Dad doesn’t want me, my stepdad is always there for my brother, he is a good dad.”

We talk about his Dad. Jordan is feeling sad about his relationship with his Dad and his hurt is palpable. He states their relationship is currently broken down after Jordan asked his Dad for some money; a request his Dad refused, and an argument ensued. “My Dad said all I ever want is money and he didn’t want to have anything to do with me…. he didn’t even send me a Xmas card Miss.” Jordan clearly feels angry and rejected, “What kid doesn’t ask for money off their Dad?”

Jordan has lots to do with his Dad’s family and proudly shows me a picture a picture of his half-sister on his phone. “My Dad doesn’t have anything to do with her either”. Despite this, his father’s family accepts him, and he has close relationships with his Aunties and Uncles. “I ring them, go around, they have taken me on their holidays.... isn't my sister tall for her age?”. It is clear family means a lot to Jordan.

I asked about his Dad’s role in his life. “He split with my Mum before I was born because he didn’t want me”. He has played parts in Jordan's life on and off since and has served time in prison.

I ask about his stepdad. Jordan immediately states he is “A much better Dad because he is always there for my little brother no matter what, he always rings him from prison”. So, he has been a father figure to you? “Yes, at first but once he had his own son, he started ignoring me and got “nasty” to my Mum”. (This is referencing the known domestic violence Jordan has witnessed. I did not pursue this)

I put it to Jordan that, on paper, his stepdad would not be considered a good role model. He had rejected Jordan, was violent and abusive to his mother and now isn't around for his son, due to a long prison sentence for a violent crime. I pose the question “Is he just better than your Dad?” “Yes, I suppose so.” It is clear being present as a father, is what Jordan values.

“I can’t believe he met the Queen.”

So, have you got any positive role models Jordan?

“Christy”, is he replies instantly with a smile. Christy is a youth mentor, a black man who grew up in care and now runs a youth mentoring company that works in the school.

Why Christy? “Because he came from nothing, and now he has a nice car and his own business….and he has met the Queen! Did you know that Miss? I didn’t believe him until he showed me the picture!” (Christy has an MBE)

Would Christy still be someone you admired if he was white? “Anyone who makes it gets my respect”.

“The police are out to get everyone especially people like me.”

Jordan reveals to me he has been stopped and searched by the police over 30 times. I cannot believe this and ask him if he is sure it is that many. He is adamant it is. “Miss, if there is a group...it’s always me they stop; they are out to get people “like me” My white mates get to walk on”. He states he has been pushed up against a car by the police. I ask why he is a target. Jordan thinks it’s because he wears designer clothes. He recalls once on the way to Trafford Centre he was stopped and searched. He has £200 cash on him and was wearing a designer coat and “man bag”. “Miss, it was my birthday money and I wanted to get new trainers. I was looking forward to it, so I’d worn my nicest stuff. They asked if I’d been robbing. What kid doesn’t get birthday money and goes to spend it? What kid doesn’t like nice clothes? It's all I ever ask for…. money and clothes”. I point out that Jordan has been found with cannabis, so how is he helping himself? “I don’t deal it though and others don’t get searched, so they don’t get caught” is Jordan’s response.

“What do you need from us Jordan?”

Jordan struggles in school. He is often demotivated and likes to put his head on the desk. Why is this? “The work is too hard. I hate algebra… What is the point? Why is work so hard, when it's so easy to rob a shop and get money?”

Jordan wants to be a joiner when he is older (though some scouts are watching him play football). His paternal Grandad has his own business and Jordan wants the same. He clearly admires his Grandad.

He wants to be able to talk when he feels angry. That sometimes he needs to take time-out to calm down. In Maths he says if the teacher is there 1-1, he gets it, but if left on his own, he just can't do it at all. He likes doing practical things, likes PE.

As we were finishing up, Jordan tells me about a time he had a glass bottle thrown at him by a group who also called him a “N-word”. He had a massive lump on his head. When was this? On a Sunday at the Trafford Centre. So, you were in school the next day? Yes. Did you tell anyone what had happened? Jordan how can we help if we don’t know stuff like that? “What's the point?”

Update 1st April 2021:

Since school re-opening, Jordan has had multiple behaviour referrals for refusing to attempt any work. He has been issued with a time-out card to help him manage his anger. He will shortly be put onto a Prince’s Trust programme and still sees Christy every week. He has however kept his “head down” but he still struggles to keep his cool and needs lots of pastoral support.

Jordan’s Mum found it very hard to read the blog, but is grateful as she has learnt things she did not know. She feels guilt abut her choices in life. She is very proud of Jordan for this piece of work.

Jordan’s father contacted Jordan last week via Instagram, Jordan showed me the messages.

“I love you son and I’m sorry”

Jordan: “No, I don’t care anymore, I don’t want anything to do with you after what you said to me”

“Ok, no problem, I won’t forget that, do your own thing, good luck”

How does that make you feel Jordan? “What kind of Dad says that? Just gives up”

Recently, an unaccompanied Syrian refugee joined the school and this appeared on Jordan’s behaviour log on the last day of term from Jordan’s pastoral manager……

“I saw Jordan playing football before lunch in PE. I spoke with him during a short break, in order to tell him well done and how impressed I was with him for his work with LCR and for the way he dealt with his issue in English yesterday.

Whilst I was waiting I watched the game. The new student, XXXX, was playing. He was clearly enjoying it, laughing and smiling, and taking full part. I saw Jordan several times applaud XXXX, help him up and generally encourage him. It was great to see. MTN witnessed it also and said how he felt Jordan had become more mature in recent weeks.”

Focus questions

“What’s the point?” is Jordan’s default position when we spoke about reporting racism? Why? And why from such a young age?

What can be put in place for a young person on the brink of a permanent exclusion?

Rejection is a theme in this story- How can we help young people who are rejected by peers? Parents?

Jordan has so much resilience in so many ways- but when it comes to schoolwork, he has very little? Why?

How can we stop stereotypes becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy? Is it too late for Jordan?

How can we stop young people feeling so disconnected from education?

Some of Jordan’s behaviours are deeply unpleasant and defiant. At what stage does Jordan need to take ownership? At what stage does a school have no choice to permanently exclude to protect staff and students?

Further reading

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/mar/24/exclusion-rates-black-caribbean-pupils-england

Find out more about the work of Christie Spurling here.

Egalitarian Red-Herrings

By Emma Turner

“I can’t believe you said that!”

“You didn’t!”

These are two phrases people often say to me when I tell them about something I’ve done within my career both in teaching and in leadership and then in terms of progression, networking or career development.

You see, I apparently have a reputation for being a little playful, or cheeky or displaying a bit of a brass neck in situations where others may have been a little more reverent or deferential.

But to me, I’m just behaving in the way I have been brought up, and until I read Erin Meyer’s “The culture map” I never really attributed this to anything other than just the way I saw things.

My father is English but my mother is Estonian. My Estonian grandparents were freed from displaced persons’ camps at the end of WWII and were asked to choose a country in which to reside (which they thought would be a temporary measure) until they could potentially return to Estonia. As it turned out, they could not return at all until the late 1980s due to Soviet Occupation. As a result, here in Leicestershire, a lively community of Estonians began to live and work in a 1940s time-capsule of culture, language and customs as they were not allowed to visit to return to their homeland, and communication with family and friends who remained in the country was highly censored and regulated.

So, I grew up in a blend of Birmingham culture – lots of trifle, meat-and-two-veg dinners and Bourneville chocolate (my paternal Grandmother having worked at Cadbury Bourneville) and on the other hand; rye bread, herring and gherkins. We grew up in a world of 2 Christmases, a first one celebrated as Estonian culture with a full roast turkey dinner on Christmas Eve (with sauerkraut and sausage too obviously) and then again, the next day as per the English tradition. I spent some of my summer running around with friends and watching cartoons but other weeks of my summers at the International Estonian summer camp based in Leicestershire where second and third generation Estonian children from across the world would stay for a week, learning the language, dancing, songs, customs and culture of a land they were not permitted to visit but where many of their family still lived.

Our household spoke predominantly English, but when any of our Estonian side of the family would visit there would be a seamless blend of Estonian and English spoken. It made me smile as I grew up that I would hear my Grandad and my mum and my uncle speaking in Estonian peppered with new vocabulary such as “microwave” or “video” or “mobile phone”. Their language was still trapped in the 1940s and so the new technology vocabulary bumped alongside their Estonian, further highlighting the shared culture in which I was growing up.

For me this was simply my life, my normal and I never paid any attention to whether or not it was having any kind of impact on my life. It is a shift as an adult that the learning you do is often informed so much more by reflecting on the past rather than the “forging ahead” thinking into the future or the next challenge or life stage which can characterise your younger learning.

It has been through this reflection, alongside the reading of Meyer’s book, that I have realised my heritage may have had far more of an impact on my career then I realise.

The Estonian community in Leicester and their large sister communities in Bradford and London were made up of survivors. Many of the original Estonian communities had to build new lives in countries and communities where they did not speak the language and didn’t know if they would ever be able to return to their homeland which they loved. Estonians are a fiercely proud but gentle people, one who have endured countless wars and occupations. In my grandfather’s and my mother’s generation, this meant that once again they were facing occupation but this time twinned with being prevented from returning. This meant that they had to hold on to what was important to them: their language, music, dancing, food, culture and history. The setting up of the Summer Camps, the formation of the Estonian “House” (a large community hub building) and the retention of key festivals and traditions whilst in what to them was a foreign country was my first lesson in holding fast to what is important to you and what you believe in, as was their emphasis on community and support.

Because so many of them were thrust into situations they did not choose, I was surrounded by people’s stories where their lives had not panned out as anticipated but they had gone on to build a new life; this thread of resilience has woven its way through my own life and my own leadership journey.

What I have also seen first-hand growing up is that building something new, taking a chance, doing something different requires just a little bit of “front” and it has also taught me that when faced with established systems and hierarchies, the quickest way to make things happen is simply to ask (politely); to engage with the people who can make things happen directly and to not be bound by convention, social niceties or hierarchies. This kind of, “What’s the worst that could happen?” and “If you don’t ask, you don’t get” attitude is not one born of showy confidence or arrogance or rudeness, simply efficiency and a belief that most people genuinely want to help others when they are asked.

None of my immediate family have had “normal” 9-5 jobs either. They have always worked incredibly hard but often for themselves or in different ways. In fact, I am the only one in my immediate family with what you might call a “proper” job and even then, I don’t work in the usual 9-5 setup.

Again though, until I read Meyer’s book, I attributed much of this to this just being our family’s “normal” but upon reading the section in the book on attitudes to hierarchies it would seem that Estonia does have a very flattened hierarchical system. It is, according to Meyer, much more egalitarian and although they respect the work and expertise of those in senior positions, are not fazed at all by the status and less likely to exhibit behaviours which reinforce these hierarchies.

Which brings me back to the, “I can’t believe you just said that” or “You didn’t!” from the beginning of this piece. I’m forever having eyebrows raised by the questions I ask, the people I approach directly or the informal way in which I chat with those in extremely senior roles. This is not because I don’t respect them; in fact, it’s quite the opposite. These people I find fascinating and want to learn from them and so that is what I do. I don’t wait for the “six degrees of separation” to land me neatly in their circles; I simply ask them. Once in conversation with them too, although I truly respect them and am fascinated by them, I don’t shy away from being light, informal and often a little cheeky or playful rather than employing a reverent and reserved approach. And this has been the same in my career around flexible working, Co-Headship and writing my books. I’ve never seen any existing system as anything other than a guide or a historical model. I’ve always championed doing things differently and not being afraid to ask what may seem like “the stupid question” or make the very untraditional request. It appears therefore, that my heritage may just have unintentionally equipped me with a bit of a gift – the egalitarian herring. You see, what I’ve found out is that in terms of professional growth, learning and creating opportunities, hierarchies can be a bit of a red herring. From my experience it’s a myth that those people in positions of less responsibility or experience should reinforce hierarchies which preclude them from accessing useful conversations, opportunities or access to networks. What I’ve learnt from unintentionally and unconsciously flattening hierarchies is that most people are delighted to be asked and to share their wisdom and experience. Most people remember what it’s like to be a bit of a Rookie or wrangling with something and most people are delighted to be asked to mentor, support or signpost opportunities for others.

So, what I would urge anyone to do if they are interested in developing themselves as a professional or a leader is to not get tripped up by the flapping hierarchical red-herring and to embrace your egalitarian Estonian.

https://erinmeyer.com/books/the-culture-map/

Being ‘White Passing’

By Rebecca Lynch

I look white. Most white people can’t tell that I am mixed-race, black and mixed-race people often can tell. People are often intrigued about my ethnicity, am I Spanish or Italian, they ask. No, I’m not. I am a mix of Irish and Nigerian. My Mom (I’m a Brummie, we say Mom) is my mixed-race parent. She doesn’t know anything about her heritage, she was born to a white mother and a very surprised, white, stepfather in the 1960s. She has four sisters, two older and two younger who are all white. My Mom was raised in a white family and has no connection with her black family at all.

This has always felt odd to me, I felt like a part of me was missing, that I didn’t truly know who I was. As a child I wanted to fit in and be like my friends. I first highlighted my hair blond when I was 11, I always wore my hair straight. This became a challenge as I got older, my Mom struggled with doing my hair which eventually led to me going to a hairdresser every week for a £5 wash and blow dry. My family wasn’t well off, but my Mom did what she could to make me happy and if that meant a weekly trip to the hairdressers then she made it happen. As I grew older, I embraced my natural hair colour and eventually my natural hair. I still wear it straight but I’m comfortable wearing my natural curls as well.

I had always wondered about my heritage, it felt too personal to explain to people why I didn’t know my background. There was a stigma attached to not knowing parents and grandparents, but as I grew older, I realised that the actions of two adults back in 1960 isn’t my responsibility. I was still left curious though. I had spoken about this a lot with my partner, and being the kind soul that he is, he ordered a heritage DNA kit one Christmas. This is when I found out that my heritage was mostly Nigerian and Irish, with a bit of North African, South Asian and Inuit as well.

Being a ‘white passing’ mixed-race person has afforded me privileges but also comes with different challenges to those who are obviously mixed-race or black. I haven’t had racist abuse directed at me, and as far as I am aware, I have never been held back professionally. In this sense I am extremely lucky to not have to endure racism. My experiences are subtler and often very uncomfortable. There have been many occasions in my life where racist comments have been made in my presence. People view me as white and therefore feel okay to refer to a group of people with the N-word, to spout their views on lazy, ignorant stereotypes and general utter nonsense. These scenarios are incredibly uncomfortable, do I stand up and challenge these views knowing that the person already hold racist views? Do I remove myself from the situation? Will I put myself in danger by speaking up? I must be honest and say that for the most part, I have walked away. Unsure of the reactions I will face if I speak up, it is easier to walk away and avoid that person or persons in the future.

I work in a school which is incredibly diverse, from the student body right through to the leadership team. The first line of our Trust’s motto is ‘Strength through Diversity’, and it is evident all the time. I feel at home in my school, our pupils are diverse, our staff are diverse. When I talk to my pupils about my heritage, they’re interested but never shocked or horrified. We often find shared backgrounds, and this is great for building relationships. Our pupils are accepting of different ethnicities, races, and religions and many of them are mixed-race. I can only hope that one day, wider society will be as kind and accepting as my pupils.

"It's not easy being mixed-race"

By Louise Cooper

It’s not easy being mixed-race, you get held up as an exotic symbol of how far society has come. Britain can't really be that racist surely? Human bridges to unite divided sides. A living balm on a fractured surface. The reality is, you can receive racism from both “sides”. You can often feel like you do not fit in anywhere, including your extended family...and you can't simply seek out other mixed-race comrades - we really are a mixed bunch and sometimes we are hard to find. This is not just about colour; this is about identity.

I am mixed-race, born to a White-British mother and Mauritian father (tiny island off coast of Africa). I’m also rather pale all things considered, and despite my dark hair and olive skin could easily fall into the bracket of “white-passing”. To some, this means I have “white-passing privilege”.

I grew up in Oldham. Oldham, a little sister Cottonopolis to Manchester, but an industrial boomtown in her own right. Oldham once had a certain Winston Churchill as her MP. Red-brick chimneys, wild moors, back-to-back terraces and salt-of-the-earth folk. At her height, Oldham was producing more cotton than France and Germany. In the 1950’s and 60’s Commonwealth citizens came to assist in keeping the spindles turning, thus Pakistani and Bangladeshi pockets began to form amongst those little terrace streets. And then it was over...decay, destitution and survival instinct, bred resentment and racial tension. Taking firm root as “them and us”; a scene sadly played out in many a northern town.

Growing up in Oldham as a white-passing person of colour was infinitely easier. So yes, white passing privilege box ticked. I could assimilate nicely amongst white working-class pubs and clubs of my youth. But I was scared…scared of being “found out”. The casual, overt racism I so often heard went unchallenged through my silence. I never stood up for fear of being discovered as a pale-faced imposter. It was nearly always directed towards the Asian community of Oldham. So, my “white-privilege” was being able to listen in... a privilege at a personal cost. The words, the bile, the venom seeped in and did their damage.

I was mostly alright, if the truth did come out my hard-to-pronounce surname usually gave me away (can we untick that box yet?). Mauritius was tropical, a luxury honeymoon destination. Some people could tell straight away and well, my Dad often gave me away. I was on the receiving end of some nasty racist abuse (always P**i). I also witnessed an appalling racist act against my lovely Dad. And my Auntie and Uncle were victims of an abhorrent attack against their home. It has left me scarred and I have only started to talk about these events in the last few years... that’s over 25 years of silence. I am not able to write about them here.

Hiding my heritage was easy, as I often resisted buying-into it myself. I am ashamed now, but I was embarrassed when my Dad spoke his primary language (Beautiful French Creole, that I cannot speak because I didn’t want to learn), embarrassed that Aunties and Uncles wore non-Western clothes; never telling anyone they were Muslims. Why? Because I heard people talk about such people as “foreign”, not like “us”, not “British”. Of course, back then I was “half-caste” which was perfectly acceptable at the time and how I would describe myself, which I can't quite believe now.

But I must say here, the vast majority of my childhood was trouble-free. I had loving family and good friends; race was rarely a thing with my friends. My goodness, how easy I had it compared to others I knew and have met in my life to date. In school there were no real issues I can recall, and I loved all stages of my education. Things got more and more diverse and studying History at Manchester University was the cherry on a well-mixed cake.

I lived in a nice, almost entirely White-British estate. Dad was accepted, as people were nice and “decent” ....…. but when the BNP came canvassing on our estate, knocking on our front door, I knew deep-down they must have felt there was political ground to be won on our doorsteps. The anxiety would set-in. That weird hot feeling in your face and that sick feeling in the pit of your stomach...

The issue was, in Oldham, there are whole different societies operating, whole worlds even and those worlds just did not mix. Secondary schools were segregated by ethnicity, streets, postcodes even. You could quite easily stay in your bit and live a nice quiet life with “no trouble”. My secondary school was in the middle of an Asian area and the “white tr*sh” comments came as I walked to the bus. Yet I also had “P**i” screamed at me from a car once. On the plus side, Dad was always able to go to the Asian Halal butchers on the Coppice estate and get the best lamb chops......what kind of privilege shall we label that?

Racial tension was never far from the surface in the more deprived areas of Oldham. There were areas that would be “no-go” for different ethnic groups. It was a tinder box; everyone knew it and the 2001 riots were no surprise, but the ferocity of the violence was truly shocking. Anyone else count burnt-out cars on their way to their Saturday job in town…or was that just me? Nevertheless, we were safe, as we did not live near the location of the rioting. But I felt more scared than ever. It divided Oldham further. Where did someone like me, fit in?

I do not live in Oldham now. Or rather I chose not to. I still love her and will never deny where I am from, though my accent won’t budge and betrays me every time anyway.

And what about now? Well now I am out-and-proud. If you can't tell I'm mixed- race, you will soon be told. But why? Because it's so much easier to have a voice as a well-educated adult. I have nothing to lose by calling out racism. I have the power to call it out, walk away.

As an educator and as a senior leader I have a platform; a sphere of influence and that is my absolute privilege. I do not and should not have the “power” to force people think a certain way, but I do seek a “power” in the sense of producing an effect; acceptance, inclusion, and equity. A nicer world for our young people.

There is much work to be done.

More on the Oldham riots can be found here:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-manchester-36369436

How Covid-19 has exacerbated racial tension in Oldham:

https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/sickening-racist-abust-people-suffered-18809954

A recent Sky report paints a bleak picture of child poverty in Oldham (Feb 2021):

https://news.sky.com/story/covid-19-i-had-my-head-down-in-shame-a-pandemic-life-in-one-of-the-uks-poorest-towns-12219505

“Why I wasn’t talking to people about race……until now."

By Marcus Shepherd

We are currently living in a period of time where the discussion about race has never been more prominent, particularly in the education world. From the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement, the public stances and statements from the majority or organisations pledging to end racism and the many powerful and inspiring voices driving the discussion around racial equality and diversity through Edutwitter.

As a mixed-race leader of a school, I am often asked to share my experiences and opinions on the issues concerning race and diversity in both education & the wider world. Although I am a confident leader & speaker, race has always been a topic which I have rarely publicly engaged with and often personally struggled with. It has only recently, since I have engaged with fellow mixed-race educators, professionals and leaders that I have felt I have found my voice.

So why you may ask (or not)? Well, it may help for me to provide some context to my upbringing. I was born to a White British mother and a Black Ghanaian father. My father was absent for most of my life and therefore I had very little contact with my Ghanaian family, culture or heritage. I have never visited Ghana (in fact I am yet to visit any country in Africa) and the closest I got to any Ghanaian cultural experiences were a few phrases of Twi, a Ghanaian language, as a result of my persistent begging of my father for him to teach me. On the rare occasions I have met other Ghanaian people who speak Twi, I always proudly state to them “Ete sen?” (‘How are you?’) to which they joyfully reply in fluent Twi. This is, unfortunately, where my cultural experience of Ghana (and often the conversation) ends.

I grew up in Coalville, a small ex-mining town near Leicester, with my White British mother, older sister and younger brother. My family (who I adore) are all White British, other than my siblings and I, and as such we were brought up in a White British culture. I do not want to suggest there is anything wrong with my experience of being raised in a White British culture, this is not the point I intend to make. However, what it did do was often create a conflict for others with regards to how I look to the world (my colour) and the culture which I present.

You may be thinking, why this is of any relevance to the question in the title of this blog? The reality is, my upbringing and subsequent experiences are the foundation of many of the reasons why I haven’t spoken about race until now. Let’s explore them a little….

Being mixed-race is a very personal & unique experience

In this statement I am not suggesting that only mixed-race people have a personal or unique experience of life. What I mean by this is that it is very difficult to generalise people’s experiences of being mixed-race as there are so many different variables which may appear irrelevant to others.

There are those that are more obvious such as:

- Which races/nationalities make up your heritage?

- What colour are you?

But then there are those more subtle, which can have a significant impact on the experiences you will face:

- Are you exposed to both cultures from your parents?

- Do you live in a community which represents both parents' heritage or just one?

- Do people make assumptions about your culture based on how you present?

- Do you feel a cultural belonging to your heritage?

- Can you pass as someone who is not mixed-race?

One of the reasons I have been reluctant to discuss race is based on people's desire to be less nuanced when identifying racial groups. People will often (with no ill intentions) ask my opinion about certain issues. They are often asking me to rule on whether a comment, opinion or system/structure is racially insensitive or offensive. I often must politely say to them that I cannot act as the spokesperson for all people of colour and that my opinion will be based on experiences and to a degree, privileges, that others have not experienced. As much as it is important to distinguish that not all people from one racial group are the same, this is even more apparent for those of us who are mixed-race.

I am very much a novice when it comes to racial inequality & diversity

People will often seek my opinion or input on the diversity issue as they will assume that I am some form of expert or better informed on the issue as a result of assumed experiences. I am not saying that this is negative, as it does allow for the discussion to be had and positive actions taken. However, my experiences have not made me particularly well informed about the racial inequality issues faced by many.

Having been raised in a White British community for my entire life, I have never really engaged, on a cultural level, with me being black. Most of my friends growing up were white, I had only two non-white teachers whilst at school and my family, whom I am close to, are all white. This created a sense of normality for me in this environment, so I never really had to consider diversity. To me my curriculum, pop culture and workplace represented me and my family. This sounds silly when I read it back, but being raised in this community and culture I did not see or notice myself as different. The unfortunate thing for me is that although I may have seen myself as fitting in and belonging to this community, often others did not, but we’ll touch on this later.

What this has meant is that I am not well versed, or even experienced ,in understanding the challenges of people who do not feel represented in domains and as such feel a degree of ignorance in this area. I believe some of this is down to the fact that my upbringing has given me an element of white-passing, which is important for me to acknowledge and not assume that this is the datum for all others in their experience of race and diversity.

I have often found it difficult to understand where I fit in the discussion

Being mixed-race can often put you in a difficult, confusing and often upsetting space. As much as I have discussed being brought up in a predominately white culture/community and not feeling out of place, racism was never far away. I have been called numerous racial slurs, ranging from derogatory insults directed to Black Africans to those intended to insult people from Southern Asia. When I began going out to pubs and clubs as a young man, I had to be careful which places I went as some establishments had less than welcoming attitudes towards me. At kick-out time I would always make my excuses about why I could not hang around and leave sharply, as I had too many bad experiences of drink leading people to want to start a physical altercation with me based on my race.

However, I felt this would all change when I moved to University. This was to be my first experience of living in a much more diverse community, and one in which people could share my experiences. Unfortunately, this was not to be the case. It was here where I first experienced being referred to as a ‘bounty’ or ‘coconut’ due to the fact that my culture did not match with the expectations that others had based on my race. It was the first time I had tried to reach out to a part of my culture I felt disconnected to and as a result I had felt further from it.

I want to be clear; these were both examples of bad experiences of a minority of people. Since my professional career has begun, I have friends and colleagues of a wide diversity of races, religions and cultures who treat me with both acceptance and respect. I do not for a minute believe or promote the view that this is exclusively the treatment of mixed-race people by these groups. But it is the unfortunate reality of my early experiences.

I often found it difficult to hear that I didn’t fully understand the black experience or that I ‘wasn't really black’. However, since I have engaged with race and fully understood the phrases ‘white passing’ and ‘white privilege’, I now understand and appreciate that my upbringing allowed me to benefit from elements of these. When using my voice to speak out and further the discussion, it is important I understand this privilege I have experienced.

It reminds me that, in most spaces in my life, I am different.

The most telling reason though comes down to self-protection. As I have discussed, I grew up seeing very few people who were not white and as such this led to me not seeing myself as being different. This was often the case, but it meant that when I was racially abused it brought the reality of my differences back to me in the most hurtful manner.

I have had numerous racists remarks made to me but the one that really hit home and awakened by engagement with race was in my previous school as Principal. I had needed to deal with a very confrontational and challenging young man and as a result he yelled, in front of the whole school, a racial slur directed at myself. I brushed it off and dealt with the situation before returning to my office. This was the first instance of racism I had experienced in a long time but in the privacy of my office I then started to cry.

I wasn’t expecting my response, but I soon realised that it didn’t matter how long I had gone without having to see myself as different, others did. I was the Principal of the school, the highest level of influence and authority in the building but in that moment, I felt vulnerable, ashamed and helpless. Those who have experienced it will understand the sick feeling in my stomach, the sense that everyone in the building was staring at me and my feeling of utter shame that came with this comment. It was in this moment that I realised that I not only had to add my voice to the discussion, but I had to use whatever influence I have to move things forward.