By Adam Vasco

Adam is a Lecturer in ITE (Primary/Early Years) at Liverpool John Moores University

It’s Coming Home… Unfortunately, when I say ‘it’ I am referring to racism and when I say, ‘coming home’, it never really went away.

It is Monday 12th July 2021. The dust is just settling on the first major final for the men’s English football team in 55 years which sadly ended in tears. Let me say this right from the outset, as is typical with many people in our city of Liverpool, I identify as “scouse” and not English. The scenes from last night’s game only further compound this. However, this rainbow-armband-wearing, free- school-meal fighting, knee-taking team had me interested. In their manager, Gareth Southgate, I had been won round by his leadership qualities, his humility, and values. It comes to something when the manager of the men’s England football team shows more leadership than the Prime Minister, but this is where we are.

As Bukaya Saka stepped up to take what would become England’s final penalty I had a sinking feeling. Not because I thought he would miss, but I knew that if he did, three black players would be held responsible. It was the first thing I said to a room full of white friends. They’re good people, that fact had not crossed their minds. This is privilege. The same privilege that was afforded to Stuart Pearce and now manager, then player, Gareth Southgate when they missed penalties in previous tournaments. Yes, they received criticism, but none of that was as a result of the colour of their skin.

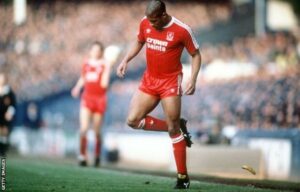

The response was inevitable. In a country where our leaders criticise taking the knee, describe Burkha-wearing women as ‘letterboxes’ and use language such as ‘picannies with watermelon smiles’, racism has once again been legitimised. For today at least, most people will share some sort of outrage or denouncing of racism. However, this is not enough and clearly, this will do little to address or change the racial inequalities that exist. One of my childhood heroes John Barnes commented;

Football can do nothing to solve the ills of the world. What we’re saying is they score, we’ll support them, and if they don’t they’ll get racist abuse. We have to stop feeling football can solves this problem. Society has to stop it.

The history books tell us we have been here before:

- In the UK alone, we can go back to the post WW1 race riots, a shortage in jobs meant Jamaican soldiers were blamed for taking ‘their’ jobs.

- Post WW2, the Bristol Bus Boycott. Black people from Africa, the Caribbean and India were asked to rebuild the country (just like my Grandfather Abe who arrived from Lagos) but were not permitted to drive council owned buses.

- The Immigration Act of 1971 stripped Commonwealth citizens of their right to remain in the UK and restricted rights, something Priti Patel is seemingly trying to do again now, and let’s not mention the Windrush generation….

- Stephen Lawrence was murdered in 1993 but the perpetrators only convicted in 2012 with the Macpherson Report describing ‘institutional racism’.

- Here, only a matter of miles from the house in which I sit there were the 1918 race riots long before the Toxteth riots of the 1980’s.

- In 2005, shortly after the birth of my son and in the Huyton community in which we lived at the time, Anthony Walker was brutally murdered in a racially motivated assault. Sadly, I could go on.

Racial inequality is not a new topic, far from it. There is some debate to exactly when the term ‘white’ was invented as part of a ruling class, but in both David Olusoga’s and Theodore W Allen’s works, it would appear that it was around the early 1600’s. The rest is quite literally history.

We need not look back any further than the start of Euro 2020 and the response to players taking the knee to see this issue is as prevalent as ever. The irony of Home Secretary Priti Patel labelling this as ‘gesture politics’ and then a matter of days later donning an England shirt for a photo op is not lost on many of us. However, as shocking as this sounds, I find myself agreeing with Priti Patel, after all, even a broken clock is right twice a day. As the England team proudly took the knee, the question I have is this. Does sport care about equality? Do these gestures have any impact and what can we learn from this in the context of education?

Nesrine Malik wrote in The Guardian

‘But still we argue over the most basic ways of showing support for these causes, such as taking the knee…. What is becoming clear is that there is broad consensus that racism is bad… but very little appetite for actually doing anything to make the world fairer or more accommodating.’

Why is that? I would suggest that this is because to do something that tackles the actual issue it would impact on the bottom line. It would dent profits and that cannot be allowed to happen. What is the bottom line in terms of education? Knowledge!

I am fortunate enough to be part of an institution which is committed to challenging racial inequality. One way in which this is happening is through an institution wide decolonisation of the curriculum (DTC). However, my fear is that without the right guidance, self-reflection, education, understanding and knowledge, this work will become an empty gesture. Now, let me be clear. I am not saying I do not believe in the decolonisation and development of anti-racist curricula, that would be insane. I am a huge fan of this work; the recent research from the Runnymede Trust highlighted that less than one percent of authors studied at GCSE English Literature area from an ethnic minority background. However, I do question whether decolonisation goes far enough. Whether that in education it has become the taking of the knee.

Educational establishments are often a direct result of colonisation. That is okay. We must not rewrite history but learn from it. However, as School’s rush to decolonise their curricular should we ask the questions who is doing that and for whom? My experiences are this is a predominantly white staff, teaching a predominantly white cohort of students so surely something is afoot somewhere?

Our own website gives some history to LJMU:

‘We can trace our roots back to the Industrial Revolution. In 1992, we became one of the UK’s new universities, taking our name from one of Liverpool’s great entrepreneurs and philanthropists, Sir John Moores. Our current incarnation as a modern civic university demonstrates that we haven’t lost the pioneering zeal of our founding fathers and like them, we still believe that ‘knowledge is power’.

‘Knowledge is power’. One could argue that the system is designed to keep that power at the hands of the powerful. The uncomfortable truth for the predominately white workforce is that education is white. It has been racialised as white. It is structurally and inherently advantaged to those who are white. That is not exclusive to education, as Reni Eddo-Lodge says in her book ‘Why I am no longer talking to white people about race’,

‘Whiteness positions itself as the norm, it refuses to recognise itself for what it is, it’s so called objectivity and reason is it’s most potent and insidious tool for maintaining power… it is a problem as we consider humanity through the prism of whiteness’.

Of course, in last couple of weeks we have seen the culture war rage on as the detriment of the white working classes was highlighted. I know, or certainly hope I am preaching to the converted here when I state the obvious fact class and race are inextricably intertwined. The racialisation of class is nothing but a culture war designed to stoke the flames of division. Or as Reni-Eddo-Lodge puts it,

‘sticking white in front of the phrase ‘working class’ is to make assumptions about race, work and poverty that compounds the currency like power of whiteness’.

Why in Liverpool are there so few teachers from diverse, not racialised as white backgrounds? Why in the institution I work in are there so few students from diverse backgrounds? Why do people from ethnically diverse backgrounds choose not to become teachers? Why is our own staff white? Why when I am writing sessions and am desperate to ensure that the materials and sources, I use are representative do I struggle to find black and brown academics writing about anything other than race? Is it some sort of invisible barrier? Or is it a system designed that way? We must acknowledge the systemic problems that are entrenched in education. Far from the being the solution, I would argue we are right at the epicentre of the problem. I am part of that problem and it hurts me to say that, after all I am of mixed-heritage. With my Nigerian grandfather, should I have been good enough to represent a country at any sport, I would’ve been a Super Eagle, no doubt about that. Although nothing on the scale of the abuse Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukaya Saka are currently facing, there have been enough events in my life which have told me that I don’t quite belong. I say this, as despite this, I acknowledge I am part of the problem, we are all part of the problem.

There is no doubt that decolonisation of curricular can be a crucial step in making meaningful change. I would urge all schools and educators to engage in this work. ‘Diversity in Schools: A Little Guide for Teachers’ by Bennie Kara is a great starting point, giving practical suggestions we can all put into our teaching. ‘Equitable Education’ by Sameena Choudry is also an essential text. As it says on the front cover, ‘What everyone working in education should know about closing the attainment gap for all pupils’. All schools and educators should buy, read, implement and integrate David Olusoga’s ‘Black and British: A Short Essential History’ into their curriculum. Colleagues should watch Pran Patel’s Ted Talk on Decolonisation of the Curriculum and all schools should challenge themselves to make sure their books are representative. The ‘I See Me’ blog by Twitter’s Mister Bodd is a great starting point for this. A colleague recently said, ‘in a sentence I want all our staff and students to make sure that representation is in all we do.’ I cannot find fault in that sentiment at all, in fact it is imperative that we must do this. It is our job!

However, DTC will not address the inequality that exists in education. It will not get more people into teaching. It will not increase the numbers of black and brown academics interested in the field of education. Therefore, the danger is that just like footballers taking of the knee that our good intentions end up as gestures or tokenistic performance politics that do not address the actual issues.

I return to the words of Nesrine Malik;

‘Liberal goodwill towards causes and general cluelessness about structural remedies mean we live in a climate where we seem to be talking about these issues all the time, creating the impression of a society saturated with sympathy and solidarity, but really quite hostile to change.’

We seem to be standing at yet another crossroads. This time it must be different, after all, how many more ‘years of hurt’ can we suffer?

References

Barnes, J. (2021) [Twitter] Monday 12th July. Available at: https://twitter.com/capitallivnews/status/1414488098243809281?lang=en (Accessed 12/7/21)

Choudry, S. (2021). Equitable Education: what everyone working in education should know about closing the… attainment gap for all pupils. S.L.: Critical Publishing Ltd.

Eddo-Lodge, R (2019). Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Kara, B. (2021). Diversity in schools. Los Angeles ; London: Corwin, A Sage Company.

Malik, N. (2021) ‘Are there limits to using celebrities to discuss race and mental health?’ The Guardian. 7th June 2021

Olusoga, D. (2020). Black and British: a short, essential history. London: Macmillan Children’s Books.